Breaking: This morning, Judge Pauley of the Southern District of New York issued an opinion granting in part and denying in part (but mostly denying) the defendant’s motion for judgment as a matter of law in Capitol Records v MP3Tunes, in which the jury had found liability for copyright infringement and awarded over $48 million in damages. The opinion is lengthy and fascinating, especially in its characterization of the parties, and particularly the defendant. This post summarizes the rulings on each issue and sprinkles in some of the court’s more colorful commentary. Continue reading

POSTS TAGGED : DMCA

Name That MP3Tune:

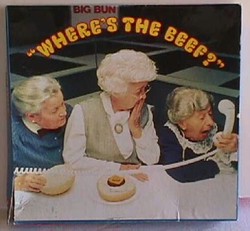

2nd Circuit Finds the Beef – Reverses Summary Judgment Grant in YouTube

On April 5, the Second Circuit issued its highly anticipated opinion in Viacom v. YouTube, reversing the District Court’s grant of summary judgment and remanding for further proceedings. Significantly, the opinion marks the first time that a court has drawn a meaningful, substantive distinction between actual and “red-flag” knowledge under the DMCA. This sets it apart from earlier DMCA opinions, including that of the Ninth Circuit in UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Shelter Capital (involving the Veoh videosharing service) and, notably, the lower court opinion in Viacom. Practitioners and ISPs now have some judicial guidance as to how to construe their rights and responsibilities under the DMCA.

Ominously for YouTube, the Second Circuit held that a reasonable jury could find that, under DMCA Section 512(c), YouTube had actual knowledge or awareness of specific infringing activity on its website. Moreover, the Second Circuit ruled that the District Court had incorrectly construed the DMCA’s control and benefit provisions in holding that the “right and ability to control” infringing activity required that the ISP have knowledge of specific, identifiable instances of infringement. Finally, the court affirmed the District Court’s holding that three of YouTube’s software functions fell within the safe harbor for infringement occurring “by reason of user storage,” and remanded for further fact-finding with respect to a fourth software function. Continue reading

Appealing YouTube: The Experts Debate!

I have been an active member of the Copyright Society of the USA for years, and am currently a member of its Executive Committee. It’s a terrific group for those interested in copyright issues, and maintains chapters throughout the country. I thought readers of this blog might like to know about this upcoming chapter event in Washington, D.C.:

The Washington D.C. Chapter of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A. is holding a membership building event on Wednesday, July 27th, 2011 from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Arent Fox LLP, 1050 Connecticut Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036, will host the event.

There will be a networking reception from 4: p.m. to 4:30 p.m, followed by the panel discussion from 4:30 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Lawyers who submitted amici briefs to the Second Circuit in the pending appeal of Viacom/Football Association Premier League v. YouTube will debate issues related to copyright safe-harbors for user generated content sites. The case will be argued soon, so don’t miss this opportunity to learn about the issues from experts.

The speakers will include:

Moderator

Robert Kasunic, Deputy General Counsel, U.S. Copyright Office

Panelists

Jonathan Band of Jonathan Band PLLC

Patrick Coyne of Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner LLP

Russell Frackman of Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP

Ron Lazebnik of Fordham University School of Law

Mary Rasenberger of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP.

Any non-member who joins the Copyright Society of the U.S.A. immediately prior to registering for the event may attend for free. Attendance is $40 for non-members and Copyright Society members. Attendance is $25 for Student members of the Copyright Society. Any Copyright Society member who invites a guest who joins the Society immediately prior to registering for the event may attend at half price.

Registration materials and a membership application are at the following link.

http://www.csusa.org/chapters/dc/CSUSA%20DC%20EVENT%20July%202011.pdf

Space is limited. Please register early. The registration deadline is extended to July 25, 2011.

Second Round

Who’s on Second? A look at secondary liability and the DMCA

A couple of weeks ago, I reprised my talk on secondary liability and the DMCA for the State Bar of California’s IP Section. I updated my original talk – initially delivered last fall to the ABA – to reflect the current status of the UMG v. Veoh and Viacom v. YouTube appeals, which in the interim were fully briefed (and, in the case of Veoh, argued). You can review the revised and updated outline here.

The outline also notes a late-breaking development in the YouTube case stemming from the United States Supreme Court’s recent decision in Global-Tech v. SEB, a patent case addressing the doctrine of willful blindness. I have posted a fuller analysis of this development over at The 1709 Blog, which you can read here.

What’s On Second?

A look at the current state of secondary liability and the DMCA

A few weeks ago, I gave a talk on secondary liability to the Copyright Subcommittee of the Intellectual Property Litigation Section of the ABA. I examined the impact of the DMCA on traditional doctrines of secondary liability and discussed two significant cases pending at the Circuit level which present knotty questions at the intersection of the statute and common law. These two cases – Viacom v. YouTube, 2d Circuit Case No. 10-3270, and UMG v. Veoh, 9th Circuit Case No. 09-5677 – offer the opportunity for meaningful development of the jurisprudence in this area.

Andy Berger, on his excellent IP In Brief blog, has posted the outline of my talk here. He has also posted his own take on “some of the noteworthy changes to secondary liability” resulting from the passage of the DMCA. Having once squared off in the courtroom against Andy, I can personally attest to the depth and sophistication of his knowledge of copyright. His posts are always worthwhile to read.

You can find my earlier posts on Viacom v. YouTube here and here. Veoh is likely to be heard before YouTube. I will post the opinions when they are available.

Where’s the Beef?

YouTube Opinion Lacks Heft

In sharp contrast to the voluminous materials submitted by the parties in support of their cross-motions for summary judgment in the Viacom v. YouTube litigation, the court’s opinion granting judgment in favor of YouTube is surprisingly lean. Indeed, a third of the 30-page opinion is devoted to verbatim quotes of the statute and legislative history. The opinion represents a resounding victory for YouTube and, by extension, the rest of the user-generated content industry (for the time being, anyway – Viacom, not surprisingly, has indicated that it will appeal the decision). But – leaving the merits of the dispute aside for a moment – it also represents a lost opportunity for a thoughtful contribution to the jurisprudence in this developing area of law.

Copyright Act Section 512(c) creates a “safe harbor” for internet service providers who allow users to upload copyrighted content to their services. The “safe harbor” shields ISPs from liability for copyright infringement “by reason of the storage at the direction of a user” of infringing material if the service provider meets certain criteria. The ISP must follow prescribed “notice and takedown” procedures to remove materials identified by copyright owners as infringing. Moreover, the ISP must neither have “actual knowledge” that material on the system is infringing nor be aware of “facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent.”

The court’s opinion centers on construing these knowledge provisions. Specifically, “the critical question is whether the statutory phrases . . . mean a general awareness that there are infringements . . . or rather mean actual or constructive knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of individual items.”

Actual vs. “red flag” knowledge

In my initial post on this decision, I stated that the court “analyzes the Section 512 safe harbor for ISPs and corresponding legislative history.” Upon a closer reading of the opinion, this turned out to be something of an overstatement. Rather, after reciting Sections 512(c) and (m) verbatim, as well as lengthy passages from the legislative history, the court simply concluded, with no discussion whatsoever, “The tenor of the foregoing provisions is that the phrases ‘actual knowledge that the material or an activity’ is infringing, and ‘facts or circumstances’ indicating infringing activity, describe knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of particular individual items. Mere knowledge of the prevalence of such activity in general is not enough.” Given the size of the case (the complaint sought $1 billion in damages), the significance of the legal issues, and the need for a well-developed body of jurisprudence to guide the ongoing development of new business models and to create settled expectations among copyright owners and users of content, it would have been nice to see a little closer parsing of the language in the statute and legislative history. Clients, in my experience, are never thrilled to be advised on the tenor of the law – they want to know what the law is, so they can act accordingly.

The one comment that the court made on the actual statutory language was in connection with subsection (m), which “explicit[ly]” states that the DMCA “shall not be construed to condition ‘safe harbor’ protection on ‘a service provider monitoring its service or affirmatively seeking facts indicating infringing activity . . .” Seizing on that language, the court noted, as a policy matter, that letting “knowledge of a generalized practice of infringement in the industry, or of a proclivity of users to post infringing materials, impose responsibility on service providers to discover which of their users’ postings infringe a copyright would contravene the structure and operation fo the DMCA.”

Having thus dispensed with statutory analysis, the court went on to recite the holdings of the Ninth Circuit and two of its district courts in cases where similarly situated defendants were found to be unaware of “facts and circumstances” sufficient to constitute red flags under the DMCA. As with its discussion of the statute itself, the court engaged in no meaningful analysis of these opinions. The court also cited favorably the Second Circuit’s opinion in Tiffany v. eBay, Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2010), a trademark case. In eBay, Tiffany sued eBay for contributory trademark infringement because eBay allow sellers of counterfeit goods to continue to operate despite knowing, generally, that counterfeit Tiffany goods were being sold “ubiquitously” on the site. The Second Circuit ruled for eBay, holding that it could not be liable unless it had knowledge of particular listings of counterfeit goods; the Viacom court concluded, “[a]lthough by a different technique, the DMCA applies the same principle. . . .”

Direct financial benefit where the ISP has the right and ability to control the infringing activity

Section 512(c) also prohibits an ISP from receiving “a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity, in a case in which the service provider has the right and ability to control such activity . . .” The parties hotly disputed whether YouTube had the right and ability to control the activity of users who uploaded infringing content, with each side devoting several pages of briefing to the issue. Again, the court’s opinion gave the issue short shrift, holding without citation or elucidation that “[t]he ‘right and ability to control’ the activity requires knowledge of it, which must be item-specific,” and citing back to the sections of the opinion addressing the knowledge requirement.

I was especially disappointed that the court did not address the question whether YouTube received a direct financial benefit from the allegedly infringing activity, though I recognize that the court did not need to reach the issue given its ruling (however cursory) on the right and ability to control the activity. But there is a bothersome discrepancy between the traditional common-law doctrine of vicarious liability and the form of it enacted in the DMCA. Recall that in Fonovisa, Inc. v. Cherry Auction, Inc., 76 F.3d 259 (9th Cir. 1996), a flea-market operator was held vicariously liable for the sale of bootleg recordings because it received a “direct financial benefit” from the infringing activity in the form of booth rental fees, admission fees, parking payments, concession stand revenues, and the like. Even though these revenues were not directly tied to the sale of infringing goods, they were held to provide a direct financial benefit because the sale of pirated recordings was a “draw” for customers.

The legislative history of the DMCA, in part, states that the drafters intended to leave “current law in its evolving state” rather than “embarking on a wholesale clarification” of the doctrines of contributory and vicarious liability – suggesting that it did not intend to modify Fonovisa and its progeny. Yet elsewhere, the legislative history states that “a service provider conducting a legitimate business would not be considered to receive a ‘financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity’ where the infringer makes the same kind of payment as non-infringing users of the provider’s service.” This statement suggests that the booth rental fees and other revenues not directly tied to bootleg sales in Fonovisa would not constitute a direct financial benefit – setting up a conflict within the legislative history and with Fonovisa.

“Where does this appeal go? It goes up.” (bonus points if you can identify the riff)

It can come as no surprise that Viacom intends to appeal, and it will be very interesting to see what the Second Circuit thinks of this opinion. I will post appeal briefs when they are available.

For those of you feeling nostalgic for the ’80s after seeing the photograph at the beginning of this post, you can view the clip of the original Wendy’s “Where’s the Beef” commercial here, thanks to one laconic judge in the Southern District of New York.

Judge Louis “Lightning” Stanton Quick on the Draw

Rules in Favor of YouTube in Viacom Suit

Today Judge Louis Stanton granted YouTube’s motion for summary judgment in the Viacom v. YouTube litigation – an incredibly quick decision in almost any case, but especially here, where the parties filed tremendously dense briefs and supporting declarations with hundreds of pages of exhibits. Viacom v. YouTube, No. 07-2103 (S.D.N.Y. filed June 23, 2010). The opinion is hot off the presses and I have not yet read it in its entirety, but in a significant holding, it analyzes the Section 512 safe harbor for ISPs and corresponding legislative history, concluding that “the phrases ‘actual knowledge that the material or an activity’ is infringing, and ‘facts or circumstances’ indicating infringing activity, describe knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of particular individual items. Mere knowledge of prevalence of such activity in general is not enough.”

There is more – I will post further thoughts once I’ve had a chance to digest the entire opinion. Hat tip to my colleague, Raffi Zerounian, for spotting this and bringing it to my immediate attention.

Viacom and YouTube Open the Kimono

Parties Publicly File Redacted Copies of Summary Judgment Motions

Today, the parties in Viacom v. YouTube, No. 07-2103 (S.D.N.Y. filed March 13, 2007) made public redacted copies of their summary judgment motions and supporting declarations, which were originally filed under seal on March 8. The volume of materials is staggering, though not surprising in such a significant and vigorously disputed case. Whatever else one concludes about the filings, there appears to be a very thoroughly developed record here. I will be posting my reactions to the filings in the coming days, but in the meantime, here are copies of the briefs and most of the declarations (not all exhibits are included).

Viacom MSJ

Hohengarten Declaration

Ostrow Declaration

Solow Declaration

YouTube MSJ

Botha Declaration

Hurley Declaration

King Declaration

Levine Declaration

Maxcy Declaration

Reider Declaration

Rubin Declaration

Schaffer Declaration

Schapiro Declaration

Solomon Declaration

Walk Declaration

Another One Bites The Dust

Court Rules Against Torrent File-Sharing Service

In another major victory for content owners over file sharers, the Central District of California found the owner and operator of a “torrent” file-sharing service liable for inducing copyright infringement in Columbia Pictures Indus., Inc. v. Fung, et al., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122661 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 21, 2009). The Fung case reflects the continued evolution of peer-to-peer file-sharing technology since the Napster service was found to be infringing nearly a decade ago. Napster maintained a centralized index of song titles available for sharing and matched a user seeking a particular song directly with a user who had a copy of it. The Grokster, KazAa and Gnutella services did not maintain a centralized index of song titles, but upon request would search users’ computers for a copy of a particular song title and then match the requester with the user who had a copy of it.

In contrast, a torrent user visits a website to find “torrent files” relating to content the user wants to find. The torrent file does not contain the actual content the user is looking for; instead, it contains metadata which allows the torrent software to find and retrieve content from individual users’ computers. When a user selects a particular torrent file for download, the torrent software then identifies multiple locations where the content resides, and downloads pieces of it from all of those locations simultaneously. This approach allows for much faster and more efficient downloading of files and lessens the bandwidth strain on participating systems.

Fung operated a number of torrent websites which provided users with the torrent files necessary to find and share copyrighted content. Under the standards enunciated by the U.S. Supreme Court in Grokster, the court found Fung liable for inducement of copyright infringement.

Secondary Liability for Foreign-Based Activity

Because the Copyright Act has no extraterritorial effect, and the servers that Fung used to maintain his websites were located in Canada, the court addressed as a threshold matter whether the Copyright Act could reach Fung’s conduct. A contributory infringer may be liable for actions occurring abroad which knowingly cause direct infringement within the United States. Accordingly, Fung’s liability hinged first on evidence that users located in the United States used his websites to transmit or retrieve copyrighted content. Though Fung argued that the plaintiffs needed to show that U.S.-based users both transmitted (uploaded) and received (downloaded) copyrighted content, the court found that either act, standing alone, could constitute the necessary direct infringement, since transmission violates the copyright owner’s distribution right and retrieval violates the copyright owner’s reproduction right.

The court found that the plaintiffs submitted “abundant evidence of infringement” using Fung’s websites. Plaintiffs’ expert conducted a statistical study showing that more than 95% of files available through the websites were either copyrighted or highly likely to be copyrighted. Plaintiffs also introduced evidence of direct infringement within the United States by tying together data reflecting the IP addresses and geographical locations of users with downloads of torrent files and sharing of corresponding copyrighted content. The court concluded that this evidence “conclusively establishes that individuals located in the United States have used Fung’s sites to download copies of copyrighted works.”

Inducing Infringement

The court then analyzed Fung’s conduct against the Grokster inducement standard: one who “distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright, as shown by clear expression or other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement, is liable for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties.” Under this standard, “mere knowledge” of infringing acts is not enough, nor are “ordinary acts incident to production or distribution.” Instead, liability is predicated on “purposeful, culpable expression and conduct.”

The court found that “evidence of Defendants’ intent to induce infringement is overwhelming and beyond reasonable dispute.” Fung conveyed a pro-piracy message to users by categorizing torrent files into browseable groups like “Top Searches,” “Top 20 Movies,” “Top 20 TV Shows,” and “Box Office Movies”; posting statements such as, “if you are curious, download this,” with a link to a torrent file for the then-recent film “Lord of the Rings: Return of the King”; and making repeated public statements acknowledging that his activities were illegal, such as, “they accuse us for [sic] thieves, and they r [sic] right. Only we r [sic] ‘stealing’ from the lechers (them) and not the originators (artists).”

Moreover, Fung, as well as various moderators of his sites, actively promoted infringement by providing users with technical assistance in downloading and viewing copyrighted works. Though Fung argued that the First Amendment protected this verbal conduct, the court held that under Grokster, his statements themselves were not illegal; rather, they were probative of an intent to infringe, and supported a finding of secondary liability.

Finally, Fung’s sites implemented a number of technical features designed to foster infringement, such as allowing users to locate and upload torrent files and automating the collection of torrent files from other sites which were well-known to contain infringing content.

As in the Napster and Grokstercases, Fung’s business model depended on “massive infringing use.” His websites generated revenue almost exclusively by selling advertising space. Revenue depended on users visiting the sites and viewing the advertising. Fung admitted that the availability of popular works drove visitors to his sites. He also solicited advertising based on the availability of such works, stating, for example, that his sites would “make a great partner, since TV and movies are at the top of the most frequently searched by our visitors.”

DMCA Defense Incompatible With Finding of Inducement

The court rejected an attempt by Fung to find refuge in the DMCA’s safe harbor provisions. The DMCA shields a service provider from liability for users’ infringement if the provider is unaware of the facts and circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent. If the provider has actual knowledge of infringement, the DMCA does not apply. “Willful ignorance” will likewise strip a provider of the safe harbor; thus, if the provider becomes aware of a “red flag” from which infringement is apparent, the provider may not invoke the DMCA.

Here, Fung plainly knew that his websites made copyrighted content available; Fung himself downloaded such material. Even though his own downloads occurred abroad, beyond the reach of the Copyright Act, he knew that U.S.-based users could access the same copyrighted content on his websites. Evidence produced by Defendants showed that approximately 25% of users were located in the United States, and at one point in time, U.S.-based users accessed Defendants’ websites 50 million times in a single month. Combined with the other evidence of infringing conduct and Fung’s state of mind, Fung could not avail himself of the DMCA. Indeed, the court held that inducement liability and the DMCA safe harbor are “inherently contradictory,” because inducement liability is based on bad-faith conduct “aimed at promoting infringement,” whereas the DMCA is based on good-faith conduct “aimed at operating a legitimate internet business.”