In sharp contrast to the voluminous materials submitted by the parties in support of their cross-motions for summary judgment in the Viacom v. YouTube litigation, the court’s opinion granting judgment in favor of YouTube is surprisingly lean. Indeed, a third of the 30-page opinion is devoted to verbatim quotes of the statute and legislative history. The opinion represents a resounding victory for YouTube and, by extension, the rest of the user-generated content industry (for the time being, anyway – Viacom, not surprisingly, has indicated that it will appeal the decision). But – leaving the merits of the dispute aside for a moment – it also represents a lost opportunity for a thoughtful contribution to the jurisprudence in this developing area of law.

Copyright Act Section 512(c) creates a “safe harbor” for internet service providers who allow users to upload copyrighted content to their services. The “safe harbor” shields ISPs from liability for copyright infringement “by reason of the storage at the direction of a user” of infringing material if the service provider meets certain criteria. The ISP must follow prescribed “notice and takedown” procedures to remove materials identified by copyright owners as infringing. Moreover, the ISP must neither have “actual knowledge” that material on the system is infringing nor be aware of “facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent.”

The court’s opinion centers on construing these knowledge provisions. Specifically, “the critical question is whether the statutory phrases . . . mean a general awareness that there are infringements . . . or rather mean actual or constructive knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of individual items.”

Actual vs. “red flag” knowledge

In my initial post on this decision, I stated that the court “analyzes the Section 512 safe harbor for ISPs and corresponding legislative history.” Upon a closer reading of the opinion, this turned out to be something of an overstatement. Rather, after reciting Sections 512(c) and (m) verbatim, as well as lengthy passages from the legislative history, the court simply concluded, with no discussion whatsoever, “The tenor of the foregoing provisions is that the phrases ‘actual knowledge that the material or an activity’ is infringing, and ‘facts or circumstances’ indicating infringing activity, describe knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of particular individual items. Mere knowledge of the prevalence of such activity in general is not enough.” Given the size of the case (the complaint sought $1 billion in damages), the significance of the legal issues, and the need for a well-developed body of jurisprudence to guide the ongoing development of new business models and to create settled expectations among copyright owners and users of content, it would have been nice to see a little closer parsing of the language in the statute and legislative history. Clients, in my experience, are never thrilled to be advised on the tenor of the law – they want to know what the law is, so they can act accordingly.

The one comment that the court made on the actual statutory language was in connection with subsection (m), which “explicit[ly]” states that the DMCA “shall not be construed to condition ‘safe harbor’ protection on ‘a service provider monitoring its service or affirmatively seeking facts indicating infringing activity . . .” Seizing on that language, the court noted, as a policy matter, that letting “knowledge of a generalized practice of infringement in the industry, or of a proclivity of users to post infringing materials, impose responsibility on service providers to discover which of their users’ postings infringe a copyright would contravene the structure and operation fo the DMCA.”

Having thus dispensed with statutory analysis, the court went on to recite the holdings of the Ninth Circuit and two of its district courts in cases where similarly situated defendants were found to be unaware of “facts and circumstances” sufficient to constitute red flags under the DMCA. As with its discussion of the statute itself, the court engaged in no meaningful analysis of these opinions. The court also cited favorably the Second Circuit’s opinion in Tiffany v. eBay, Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2010), a trademark case. In eBay, Tiffany sued eBay for contributory trademark infringement because eBay allow sellers of counterfeit goods to continue to operate despite knowing, generally, that counterfeit Tiffany goods were being sold “ubiquitously” on the site. The Second Circuit ruled for eBay, holding that it could not be liable unless it had knowledge of particular listings of counterfeit goods; the Viacom court concluded, “[a]lthough by a different technique, the DMCA applies the same principle. . . .”

Direct financial benefit where the ISP has the right and ability to control the infringing activity

Section 512(c) also prohibits an ISP from receiving “a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity, in a case in which the service provider has the right and ability to control such activity . . .” The parties hotly disputed whether YouTube had the right and ability to control the activity of users who uploaded infringing content, with each side devoting several pages of briefing to the issue. Again, the court’s opinion gave the issue short shrift, holding without citation or elucidation that “[t]he ‘right and ability to control’ the activity requires knowledge of it, which must be item-specific,” and citing back to the sections of the opinion addressing the knowledge requirement.

I was especially disappointed that the court did not address the question whether YouTube received a direct financial benefit from the allegedly infringing activity, though I recognize that the court did not need to reach the issue given its ruling (however cursory) on the right and ability to control the activity. But there is a bothersome discrepancy between the traditional common-law doctrine of vicarious liability and the form of it enacted in the DMCA. Recall that in Fonovisa, Inc. v. Cherry Auction, Inc., 76 F.3d 259 (9th Cir. 1996), a flea-market operator was held vicariously liable for the sale of bootleg recordings because it received a “direct financial benefit” from the infringing activity in the form of booth rental fees, admission fees, parking payments, concession stand revenues, and the like. Even though these revenues were not directly tied to the sale of infringing goods, they were held to provide a direct financial benefit because the sale of pirated recordings was a “draw” for customers.

The legislative history of the DMCA, in part, states that the drafters intended to leave “current law in its evolving state” rather than “embarking on a wholesale clarification” of the doctrines of contributory and vicarious liability – suggesting that it did not intend to modify Fonovisa and its progeny. Yet elsewhere, the legislative history states that “a service provider conducting a legitimate business would not be considered to receive a ‘financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity’ where the infringer makes the same kind of payment as non-infringing users of the provider’s service.” This statement suggests that the booth rental fees and other revenues not directly tied to bootleg sales in Fonovisa would not constitute a direct financial benefit – setting up a conflict within the legislative history and with Fonovisa.

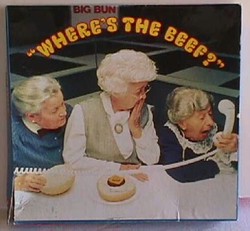

“Where does this appeal go? It goes up.” (bonus points if you can identify the riff)

It can come as no surprise that Viacom intends to appeal, and it will be very interesting to see what the Second Circuit thinks of this opinion. I will post appeal briefs when they are available.

For those of you feeling nostalgic for the ’80s after seeing the photograph at the beginning of this post, you can view the clip of the original Wendy’s “Where’s the Beef” commercial here, thanks to one laconic judge in the Southern District of New York.